Concepts, Terms, and Definitions

Team Science

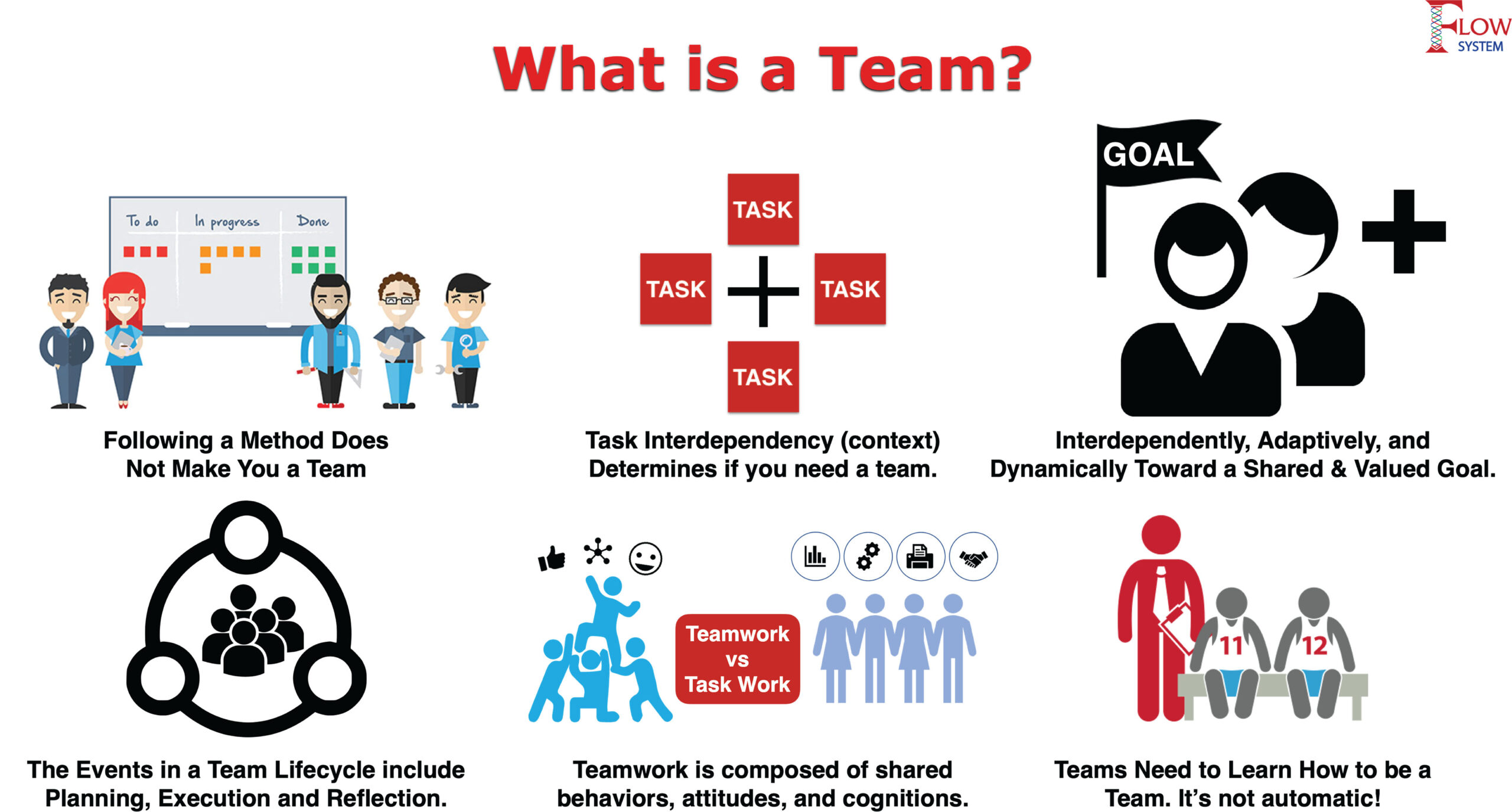

Why do we actually need a team? Is it because the task requires more resources than any one person can provide? Or because diverse skills and perspectives are required to accomplish the work? Or because flexibility is needed to keep pace with a rapidly changing context? Or because you want to provide a setting in which individual members can hone their personal capabilities through interactions with others? If non of these reasons applies, there probably is no need for the extra work and leadership attention that it takes to create and support a team.

(Hackman, 2011, p. 27)

Reference

Hackman, R. J. (2011). Collaborative intelligence: Using teams to solve hard problems. Berrett Koehler.

TEAMS

TEAM/GROUP LEARNING

COGNITION

Team

Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp, & Gilson (2008) utilized Kozlowski and Bell’s (2003) definition:

Collectives who exist to perform organizationally relevant tasks, share one or more common goals, interact socially, exhibit task interdependencies, maintain and manage boundaries, and are embedded in an organizational context that sets boundaries, constrains the team, and influences exchanges with other units in the broader entity. (p. 411)

Teamwork

“Teamwork describes how they [team members] are doing it with each other” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 357).

Taskwork

“A teams interactions with tasks, tools, machines, and systems (Bowers, Braun, & Morgan, 1997: 90)”, (as cited in Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 357).

“Taskwork represents what it is that teams are doing” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 357).

Team Effectiveness

“Largely a function of interaction processes and emergent states (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006; Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001); both are considered mechanisms linking inputs such as leadership, training, and composition to valued team outcomes (Mathieu et al., 2008)” (as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 33).

Team Interdependence

Refers to the “extent to which team members cooperate and work interactively to complete tasks” (Stewart & Barrick, 2000, p. 137).

Team Mental Models

Refers to an organized understanding of relevant knowledge that is shared by team members. Team members’ shared, organized understanding and mental representation of knowledge about key elements of the team’s relevant environment.

Team Performance

An objective or subjective judgment of how well a team meets valued objectives.

Team Processes

Describes the nature of team member interaction.

“Mediating mechanisms linking such variables as member, team, and organizational characteristics with such criteria as performance quality and quantity, as well as members’ reactions” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 356).

“We define team process as members’ interdependent acts that convert inputs to outcomes through cognitive, verbal, and behavioral activities directed toward organizing taskwork to achieve collective goals” (Marks, Mathieu, & Zaccaro, 2001, p. 357).

Team Self-leadership

“The extent to which teams have the freedom and authority to lead themselves independent of external supervision” (Stewart & Barrick, 2000, p. 139).

Team Self-correction

Consideration of corrective feedback and group reflection as critical team learning behaviors, team self-correction has been identified as an important contributor of team mental models. Specifically, team self-correction refers to the natural tendency of a team to debrief following a performance event by correcting team attitudes, behaviors, and cognition.

Team Types

Most taxonomies of team type distinguish team tasks that are largely informational from those with high behavioral components.

- Decision-Making Teams: Teams whose tasks involve processing information and making decisions (e.g., those who do knowledge work).

- Action Teams: Teams performing time-sensitive tasks requiring members to coordinate actions and perform physical tasks.

- Project Team: Teams involved in both informational-knowledge work and behavioral action.

References

DeChurch, L. A. & Mesmer-Magnus, J. R. (2010). The cognitive underpinnings of effective teamwork: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95 (1), 32-53. doi: 1037/a0017328

Marks, M. A., Mathieu, J. E., & Zaccaro, S. J. (2001). A temporally based framework and taxonomy of team processes. The Academy of Management Review, 26, 356-376. doi:10.5465/AMR.2001.4845785

Mohammed, S. & Dumville, B. C. (2001). Team mental models in a team knowledge framework: expanding theory and measurement across disciplinary boundaries. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 89-106. doi:10.1002/job.86

Stewart, G. L., & Barrick, M. (2000). Team structure and performance: Assessing the mediating role of intrateam process and the moderating role of task type. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 135-148. doi:10.2307/1556372

Adaptive Learning

Reacting almost automatically to stimuli to make changes in process and outcome as a coping mechanism.

- Facilitating Adaptive Learning: To encourage adaptive learning, group leaders or facilitators need to focus on stimuli, encourage group identification, provide resources, and give feedback.

- They must provide or direct attention toward strong stimuli for change.

- Encourage members to identify with the group.

- The leader must provide support and resources to make necessary changes.

- The leader needs to provide regular feedback to the group on task processes and outcomes.

- Learning Outcomes:

- Reducing / eliminating external pressures

- Maintaining homeostasis and constancy within a changing environment

- Instituting changes in group operations, structure, etc., in response to changes in the environment or to feedback.

Generative Learning

Proactively learning and applying new skills, knowledge, behaviors, and interaction patterns to improve the group’s performance.

- Generative Learning entails:

- A mastery learning orientation;

- Self-efficacy derived from learning from others;

- Andragogy (adults who are ready to learn and are responsible for their own learning).

- Facilitating Generative Learning: Leaders and facilitators can stimulate generative learning by leading the group through a mission- and strategy-setting process similar to that undertaken by top management groups.

- Help groups open their boundaries

- Understand their developmental stage

- Enhance their meta-systems perspective

- Processes for supporting generative learning

- Helping members locate resources

- Identify best practices

- Survey the competition

- Provide the group with training in new methods and the chance to try new approaches

- Capturing generative learning

- Helping members reflect on the learning process

- Reflect on ways to evaluate change

- Reflect on how to codify changed business practices

- Assess efficiency of group operations

- Learning Outcomes:

- Instituting new procedures to meet current and future contingencies

- Incorporating new skills, behaviors, and knowledge into group practices

Group Learning

- Viewed as an aggregate of individual learning:

- Group learning occurs when individual group members create, acquire, and share unique knowledge and information.

- Viewed as a process:

- A process for effecting change in interactions as members acquire, share, and combine knowledge; test assumptions; discuss differences openly; form new routines; and adjust strategies in response to errors.

- Views the group as a system:

- A dynamic system in which learning processes, the conditions that support them, the individuals in the group, and the group behaviors change as the group learns.

- Viewed as a cycle of activities:

- Group learning has been viewed as a cycle of activities including reflective communication, experimentation, and knowledge codification.

Group Continuous Learning (a process and systems view)

- A deepening and broadening of the group’s capabilities in

- (re)structuring to meet changing conditions;

- adding and using new skills, knowledge, and behaviors; and

- becoming an increasingly sophisticated system through reflection of its own actions and consequences.

Readiness to Learn

How a group comes to recognize that stimuli for learning are occurring and that the group needs to change, learn something in order to accomplish its work, and to actually make a decision to take action.

Transformative Learning

Re-creating or altering the group’s purpose, goals, and-or structure or in other ways changing the core nature of the group.

- Facilitating Transformative Learning: Transformative learning methods include holding practice sessions, designing experiments, and comparing the outcomes of old and new practices.

- Leaders can give the group time to practice new routines, be a role model for new behaviors, evaluate their effectiveness, and improve.

- Unfreeze the group and bring in needed talents, positive attitudes, and fresh perspectives.

- Leaders and facilitators can encourage transformative learning by

- Defining change initiatives as transformational,

- Encouraging critical reflection,

- Helping to assess the current group culture and determine what elements must change to align with a new strategic direction, and

- Encouraging discussion about what it means to respect and value a diversity of disciplines and perspectives.

- Learning Outcomes:

- Introducing wholly new behaviors and outcomes

- Adopting new goals

- Creating new products or services

- Going after new markets

- Forming new alliances

References

London, M. & Sessa, V. I. (2007). How groups learn, Continuously. Human Resource Management, Winter, 46, 651-669. Doi: 10.1002/hrm.20186

Salas, E., Benishek, L., Coultas, C., Dietz, A., Grossman, R., Lazzara, E., & Oglesby, J. (2015). Team training essentials: A research-based guide. Routledge.

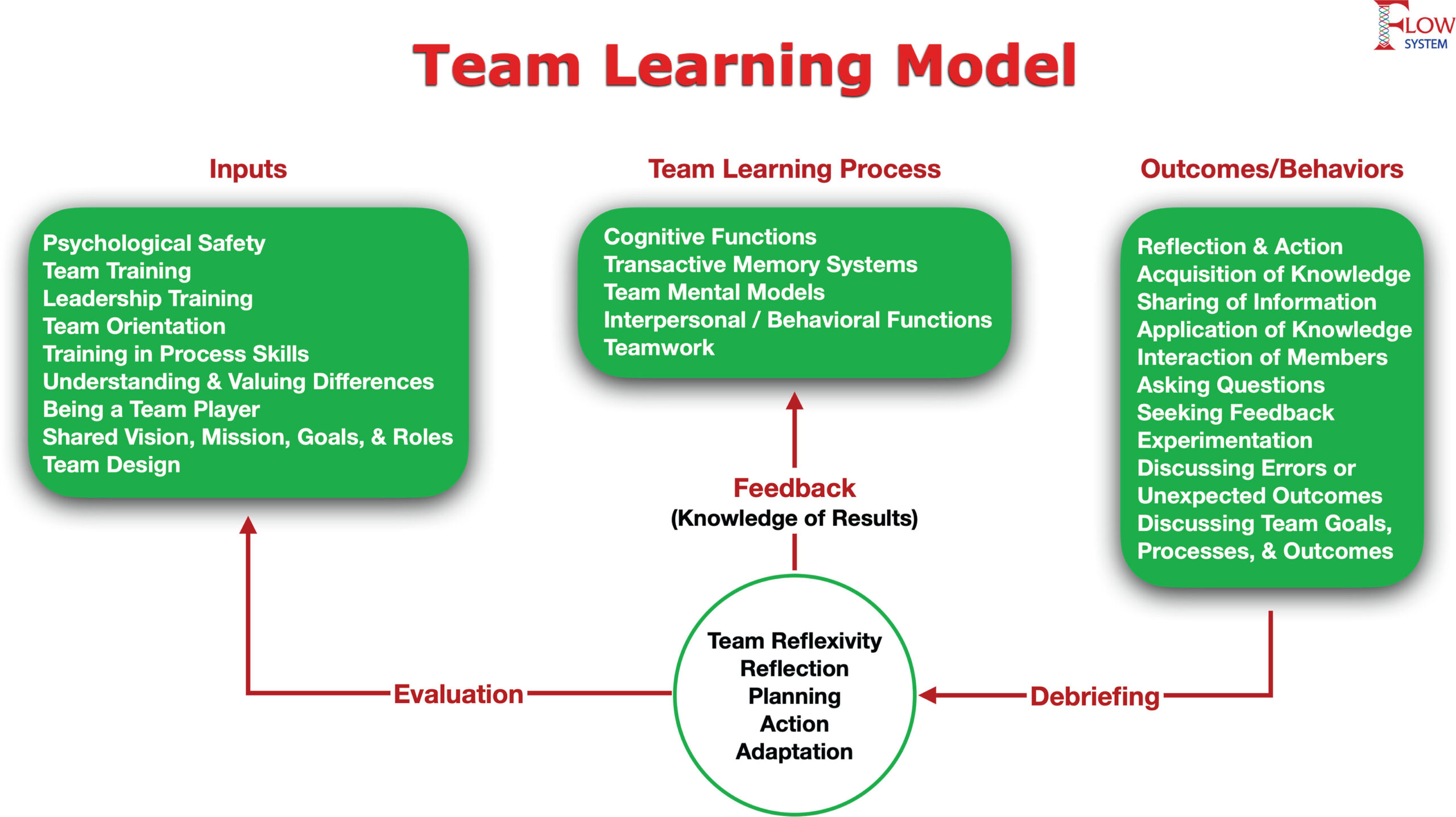

Team Cognition

“An emergent state that refers to the manner in which knowledge important to team functioning is mentally organized, represented, and distributed within the team and allows team members to anticipate and execute actions” (Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006; as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 33).

Two overarching dimensions of cognition are represented by the literature: task-related cognition and team-related cognition (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010; Mathieu et al., 2000).

Task-Related Cognition

“Task-related models refer to features of the team’s job, major task duties, equipment, and resources typically derived from a detailed task analysis” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 36).

Team-Related Cognition

“Team-related models include features of how team members interact and are interdependent with one another” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 36).

Form of Cognition

“The way cognition is elicited and represented” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 35).

“Type of similar meaning, understanding, or interpretation among team members (Rentsch et al., 2008)” (as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 40).

“Research on team cognition has focused on three different forms of cognition: (a) perceptual, (b) structured, and (c) interpretive” (Rentsch et al., 2008, as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 35).

Perceptual Cognition

“Perceptual cognition models team members’ beliefs, attitudes, values, perceptions, prototypes, and expectations, but ‘does not provide a deep understanding of causal, relational, or explanatory links’” (Rensch et al., 2008, p. 146; as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 36).

Structure Cognition

“Structured cognition attempts to capture the organization of a team’s knowledge without modeling the content or amount of a given type of perception. Structured cognition focuses on the pattern of knowledge arrangement and then models the collection of knowledge patterns within a team” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 36).

Cognitive Accuracy

Refers to the extent to which teammates’ mental models match “correct” or target cognitive structures.

Cognitive Consensus

Refers to similarity among group members regarding how key issues are defined and conceptualized. Cognitive consensus deals with the interpretation of the information, how it is viewed by the group and the opinions that are held about it.

Cognitive Similarity-Congruence

Refers to the extent to which teammates’ cognitive structures match one another.

Content of Cognition

“Domain of knowledge contained in the team’s collective cognition (Marks et al., 2002; Rentsch et al., 2008)” (as cited by DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 40).

Emergent States

“Emergent states are cognitive, motivational, and affective properties of teams…. Emergent states describe conditions that dynamically enable and underlie effective teamwork” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 33).

“Team cognition is a bottom-up emergent construct, originating in the cognition of individuals; the cognition of individuals present within a team manifests as a pattern, which ultimately constitutes the team cognition construct (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000)” (as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 35).

Nature of Emergence of Cognition

“Multilevel process whereby individual elemental cognitive content combines to constitute collective cognition (Kozlowski & Klein, 2000)”, (as cited in DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 40).

Compositional Emergence

“The individual-level building blocks are similar in form and function to their manifestation at the team level” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 35).

Compilational Emergence

“The construct manifested at the team level is different in form to the individual-level counterpart” (DeChurch & Mesmer-Magnus, 2010, p. 35).

Mental Models

Mechanisms whereby humans are able to generate descriptions of system purpose and form, explanations of system functioning and observed system states, and predictions of future system states.

Transactive Memory

Refers to the idea that memory is a social phenomenon, and individuals in continuing relationships often utilize each other as external memory aids to supplement their own limited and unreliable memories. Transactive memory is a set of individual memory systems which combines the knowledge possessed by particular members with a shared awareness of who knows what – each member keeps current on who knows what.

Information Sharing

Examines information pooling behaviors in groups. In principle, groups are capable of producing better decisions by pooling information. In practice, however, collective sampling dynamics promote the rehashing of shared information at the expense of pooling unshared information. Group discussion is biased in favor of shared information, as shared information is more likely to enter discussion than unshared information. Shared information is held by all group members before discussion begins, whereas unshared information is only held by one group member prior to discussion.

Motivational States

Team members’ collective reaction to interpersonal aspects of team functioning (e.g., cohesion, collective efficacy; Salas et al., 2015).

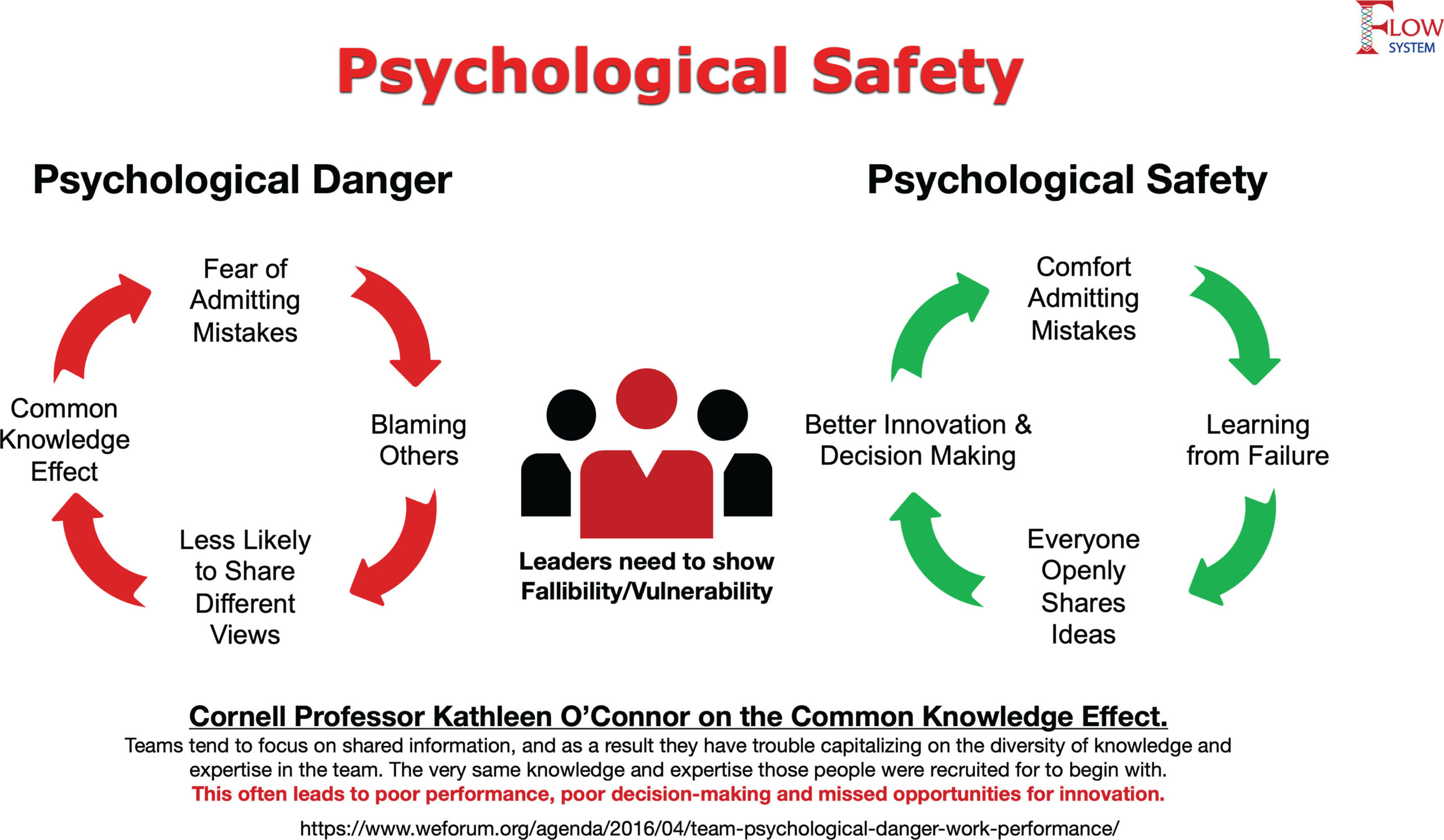

Psychological Safety

Shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking – contributes to team learning behaviors such as seeking feedback, sharing information, experimenting, asking for help, and talking about errors.

Teams – General/Miscellaneous

Group Learning

Group learning is defined in terms of both processes and outcomes of group interaction. Emphasizing processes, learning is conceptualized as an ongoing process of reflection and action, characterized by asking questions, seeking feedback, experimenting, reflecting on results, and discussing errors. As an outcome, group learning refers to relatively permanent changes in the knowledge and performance of an interdependent set of individuals associated with experience.

Realized Consensus

The level of similarity among team member’s individual belief structures.

Realized Coverage

The range of belief structures voiced during a discussion.

Learning Theories

Argyris’ single-loop learning and double-loop learning

Chris Argyris and Donald Schon have written extensively about he difficulties and importance of overcoming the natural tendency to resist new learning that challenges existing mental schema from prior experience. Argyris labels learning as either “single-loop” or “double-loop” learning.

- Single-Loop Learning: Learning that fits prior experiences and existing values, which enable the learner to respond in an automatic way.

- Double-Loop Learning: Learning that does not fit the learner’s prior experiences or schema. Generally it requires learners to change their mental schema in a fundamental way. (Knowles, Holton III, & Swanson, 2005, p. 190).

Schon’s knowing-in-action and reflection-in-action

- Knowing-in-action: The somewhat automatic responses based on a person’s existing mental schema that enable him or her to perform efficiently in daily actions.

- Reflection-in-action: The process of reflecting while performing to discover when existing schema are no longer appropriate, and changing those schema when appropriate (Knowles et al., 2005, p. 190).

Schema Theory

- Schema are the cognitive structures that are built as learning and experiences accumulate and are packaged in memory (Knowles et al., 2005, p. 190).

- Three different modes of learning in relation to schema; accretion, tuning, and restructuring (p. 191).

- Accretion is typically equated with learning of facts and involves little change in schema.

- Tuning involves a slow and incremental change to a person’s schemata.

- Restructuring involves the creation of new schema (p. 191).

Information Processing Theory

Prior knowledge acts as a filter to learning through attentional process. Learners are likely to pay more attention to learning that fits with prior knowledge schema and, conversely, less attention to learning that does not fit (Knowles et al., 2005, p. 191).

Reference(s)

Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2005). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Elsevier.